His Last Mission of World War II

The mission was supposed to have been cancelled at the last minute. The Germans had moved anti-aircraft guns from Budapest to Vienna because of the Russian advance in the East. But, Brigadier General George R. Acheson, the commander of the 55th Bomb Wing decided the mission to Vienna was worth the risks and losses. [1] The weather was poor, forcing the bombers to fly at 16,000 feet instead of the typical 22,000 – 24,000 feet altitude. [2]

The mission was supposed to have been cancelled at the last minute. The Germans had moved anti-aircraft guns from Budapest to Vienna because of the Russian advance in the East. But, Brigadier General George R. Acheson, the commander of the 55th Bomb Wing decided the mission to Vienna was worth the risks and losses. [1] The weather was poor, forcing the bombers to fly at 16,000 feet instead of the typical 22,000 – 24,000 feet altitude. [2]

The B-24 Liberators of the 780th Bombardment Squadron were in formation flying into the heavy flak. The B-24 flown by Lieutenant Richard C. Klug took a direct hit from flak, causing the bomb bay to burst into flame, members of the crew bailing out while the airplane disintegrated in the air. The formation continued on to the target. [3] The B-24 piloted by Lieutenant Everett Steiner dropped their bomb load. In his typewritten, confidential after action report, Lieutenant Steiner described the moments following the bomb run succinctly. “The formation had just dropped its bombs and we were losing altitude rapidly and taking evasive action to clear the flak area as quickly as possible. Our ship received a hit in the No. 2 engine, and, after extreme difficulty, we brought the ship under control.” [4]

In the nose of the B-24 though, sat Lieutenant Alvin “Al” Hyman. The brown haired, hazel eyed navigator from New York stood slightly over 6 feet tall. When the Liberator was hit, the veteran of 10 bombing missions over Greece and Ploesti, Romania went through the bail out procedures ingrained through training. He removed the catches on the hatch near the front landing gear and along with Lieutenant Eugene Zarek dropped through into the rushing airstream. Sergeant William Dayton, in the tail gunner position observed, “No. 2 engine was running away and [Lieutenant Steiner] was valiantly trying to get the ship in control which he eventually succeeded in doing. The two officers who bailed out passed right under the tail of the plane and I saw both of their chutes open. We were just about out of the flak area, and in my opinion they stood a good chance of reaching the ground safely.” [5]

Underneath the parachute, it’s easy to imagine the fear running through the Jewish Lieutenant’s mind as he floated to German controlled territory. Landing about 100 yards outside a German military base, Lieutenant Hyman was immediately taken prisoner. [6]

The Road to Pantanella

Lieutenant Alvin Hyman’s Aircrew Wings

Born November 18, 1924 in Brooklyn, NY, Alvin Gerald Hyman was working at Mike’s Shoe Store in Bayonne, New Jersey when he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force in November 1942. [7] He applied for Aviation Cadet School in February, and received training at the College Training Attachment at Massachusetts College near Northampton. He tested for pilot trainee in Nashville, and was assigned to Maxwell Air Field near Montgomery, Alabama. [8]

Lieutenant Hyman stated that, “His primary flight training was in a PT-17 Stearman. He washed out of pilot training when flying more advanced aircraft.” While he did not earn his pilot’s wings, the circuitous path he took to become a U.S. Army Air Force aviator led to him earning three aeronautical ratings. Gunnery School at Bellingham Field, Washington earned him Air Crew Wings. He applied to Navigator Training which he graduated at Selman Field outside Monroe, Alabama. There he was rated a Navigator and an Observer. After receiving B-24 Familiarization Training at March Field, California; Lieutenant Hyman was shipped out of Newport News, Virginia to join the 780th Bombardment Squadron at Pantanella, Italy. [9]

Gone to War

Lieutenant Alvin Hyman’s Observer Wings

Located in the Foggia-Bari region of Southern Italy, the base at Pantanella was approximately 12 miles from the nearest towns of Canosa and Cerignola. Lieutenant Hyman remembers it as “a tent city with a steel mesh runways in the middle of agricultural land.” [10] Joining the veteran 780th, Lieutenant Hyman flew a total of 10 missions before his fateful eleventh mission over Vienna, Austria.

Prisoner of War Experiences

Lieutenant Alvin Hyman’s Navigator Wings

“He said he wore his Navigator Wings mostly as he felt

it was most appropriate for what he did.” — Gary Bettcher

After being captured on landing in Austria, Lieutenant Al Hyman was taken to the Old Castle in Nuremberg. There, the Germans believed him to be a radar navigator, so he was interrogated for several weeks before being sent to Stalag Luft III. Stalag Luft III was run by the Luftwaffe as a POW camp for Allied aviation officers and was known for the “Great Escape” of March 1944. Fifteen men were in a room of bunks stacked 4 high “with only straw for a mattress” with a wood stove for heat. Lieutenant Hyman remembers being given small loaves of bread. The prisoners would stick them to the side of the wood stove, which would toast the wet, heavy bread. [11]

The night of January 27, 1945 – with Russian soldiers advancing on Stalag Luft III – Colonel Charles G. Goodrich, the senior American Officer, issued orders to his fellow prisoners. “The Goons have just given us 30 minutes to be at the front gate! Get your stuff together and line up!” The march was to take place in the “coldest part of the year” with freezing temperatures and 6 inches of snow on the ground. [12] Lieutenant Hyman remembers the evacuation:

“The German guards were few and were very weak, however the POWs were concerned that if the guards dropped out because of exhaustion the German Army troops may think they were escaping and shoot them all. The POWs offered to carry the Germans’ packs and even their guns to ensure they wouldn’t drop out. The first night they found a barn where the German guards could rest. At one time while the 1500-2000 prisoners were being marched down the road, a German donkey cart approached from the opposite direction forcing the prisoners to move to boeth sides of the road to let it pass. Not understanding what was happening, the German guards panicked and began shooting. One American officer stood up in the middle of the fracas and yelled to the POWs to stand up and raise their arms to show the Germans it wasn’t their intent to escape. He was a very brave man.” [13]

The prisoners were held at Stalag XIII-D near Langwasser-Nuremberg. Lieutenant Hyman recalled the time there as being “held there for 1 ½ months. Food was scarce as they didn’t have Red Cross support.” [14] The Schutzstaffel or “SS” then took control of all allied prisoners of war to use as hostages and bargaining chips as the war drew to a close. In addition to the forced marches they prisoners had already endured, the now malnourished prisoners had to undertake another forced march to Stalag VII-A at Moosburg, Bavaria.

Liberated

On the morning of April 29, 1945, Colonel Paul S. Goode, Group Captain Willets of the Royal Air Force – both POWs at Stalag VII-A – a SS Sturmbannfuhrer (Major), and a representative of the International Red Cross under a white flag met with US Army Brigadier General Charles H. Karlstad. The Sturmbannfuhrer carried a proposal from the German Area Commander. The proposal called for an armistice around Moosburg while the German and Allied governments determined the disposition of the “Allied prisoners of war in [the vicinity of Moosburg].” Brigadier General Karlstad contacted his superior, Major General Albert C. Smith, to present the German proposal. If an armistice was declared, the 14th Armored Division would not be able to achieve their objective of seizing a bridge over the Isar River. Major General Smith rejected the proposal and issued an ultimatum, complete surrender of the German military in the area around Moosburg. He also ordered Brigadier General Karlstad to lead his Combat Command A into Moosburg to seize the bridge and liberate the prisoners. [13]

Once the delegation from Stalag VII-A departed the headquarters, General Karlstad issued the order for the attack to commence. Once the units of Combat Command A were in position, they attacked down the main road between Mauern and Moosburg. With such a large POW camp in the area, Combat Command A did not use the artillery of the 500th Armored Field Artillery Battalion in the attack. [14]

Colonel Goode and Group Captain Willets arrived back at the camp, and began to inform their fellow prisoners that an armored unit would be coming to free them. Fire from the nearby battle came into the camp, scattering both prisoners and SS guards. Before the sun set, Wehrmacht Oberst (Colonel) Otto Burger surrendered the camp to General Karlstad. A U.S. Soldier raised the American Flag over the prisoners to a resounding cheer. An U.S. Army Air Force Lieutenant kissed one of the 47th Tank Battalion tanks stating, “God damn, do I love the ground forces.” [15]

Lieutenant Hyman was one of over 110,000 allied prisoners liberated from captivity at Stalag VII-A. He stated his liberation date (likely due to processing so many liberated prisoners) was May 4, 1945. He remembers General Patton came to the camp to speak with the POWs. “It was a day to remember.” After liberation, Lieutenant Hyman was taken to France by train before being shipped home to the United States. [16]

Aftermath

After the War, “Al” Hyman transferred into the fledgling Air Force Reserve in 1948. He married Ms. Marcia Singer and together they had two children. After graduating from UCLA with a MBA, he worked for Northrup on missile projects as a Process Industrial Engineer. Despite the hardships of being a Prisoner of War, he triumphed over everything Nazi Germany had thrown at him.

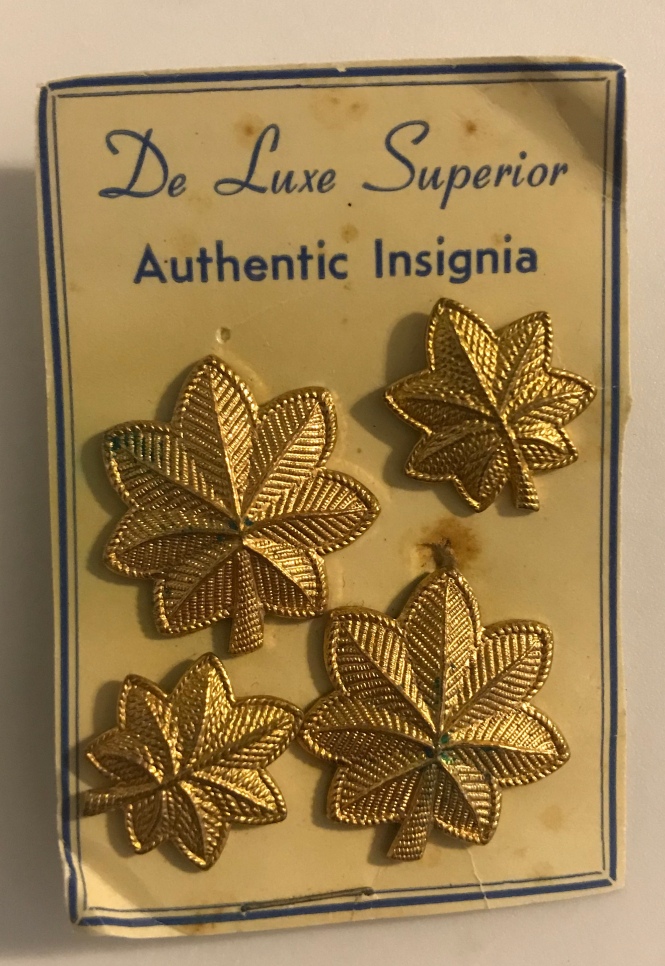

“Al” Hyman retired from the Air Force Reserve in 1969 as a Lieutenant Colonel. Interviewed by Gary Bettcher in his home at Friendship Village in Bloomington, Minnesota; he entrusted his three sets of sterling silver wings from World War II and the Major’s rank insignia he wore in the Air Force Reserves to Mr. Bettcher. They are now preserved for posterity and future generations in my collection. A physical reminder that regardless of what challenges Americans face, we can triumph.

SOURCES:

1.) 780th Bombardment Squadron (H), 465th Bombardment Group (H): In World War II (1943-1945) Pantanella, Italy. Accessed Online. http://465th.org/History/PDFs/780th%20History.pdf Pg. 13

2.) Bletcher, Gary. “2nd Lieutenant Alvin (Al) G. Hyman’s Story.” Interview conducted May 21, 2013.

3.) 780th Bombardment Squadron (H), 465th Bombardment Group (H): In World War II (1943-1945) Pantanella, Italy. Accessed Online. http://465th.org/History/PDFs/780th%20History.pdf Pg. 13

4.) Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs) of the US Army Air Forces, 1942 – 1947. The original records are located in Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General in the National Archives. Accessed online at Fold3.com. Accessed 11 Apr 2020.

5.) Ibid.

6.) Bletcher, Gary. “2nd Lieutenant Alvin (Al) G. Hyman’s Story.” Interview conducted May 21, 2013.

7.) The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for New Jersey, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 311

Source Information:

Ancestry.com. U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

8.) Bletcher, Gary. “2nd Lieutenant Alvin (Al) G. Hyman’s Story.” Interview conducted May 21, 2013.

9.) Ibid.

10.) Ibid.

11.) Ibid.

12.) “The Story of Stalag Luft III. Air Force Humanities Institute Virtual Museum. http://www.comstation.com/afhi/museum/stalag/march.html Accessed 14 April 2020.

13.) Lankford, Jim. “The 14th Armored Division and the Liberation of Stalag VIIA.” National Museum of the U.S. Army. https://armyhistory.org/the-14th-armored-division-and-the-liberation-of-stalag-viia/ Accessed online 14 Apr 2020.

14.) Ibid.

15.) Ibid.

16.) Bletcher, Gary. “2nd Lieutenant Alvin (Al) G. Hyman’s Story.” Interview conducted May 21, 2013.